Nero Redivivus

Chapter Five

THE BONFIRE OF THE VANITIES

… with usura, sin against nature,

is thy bread evermore stale rags

is thy bread dry as paper,

with no mountain wheat, no strong flour…

They have brought whores for Eleusis

Corpses are set to banquet

at behest of usura.

- Ezra Pound, Canto

XLVI

Our Daily Bread

“Give us this day our daily bread…”, recites the Lord’s Prayer, the

single most important prayer in Christendom, and the only one bequeathed to us

by Jesus himself. The most ancient and

sacred of human foods, bread is transubstantiated in the ritual of Roman

Catholic Communion into the very Body of Christ, in which every living soul is

subsumed. For the Jews, unleavened bread

plays a central role in their Passover feast, while for the Moslems, bread

represents Life itself, as the poet Rumi writes:

Buried in the earth, a kernel of wheat

is transformed into tall stalks

of grain.

Crushed in the mill, its value

increases,

and it becomes bread,

invigorating to the soul.

Ground in the teeth, it becomes

spirit, mind,

and the understanding of reason…

Wheat, the traditional Staff of Life, is older than human civilization

and actually “co-evolved” along with our pre-human ancestors over a period of

many millennia. And yet, over the past

50 years, the natural wheat which nurtured countless generations before us has

virtually disappeared, replaced by a hybridized grain that calls itself

“wheat”, but has about as much in common genetically with real wheat as

chimpanzees have with humans. Instead of

the “tall stalks”, standing some four feet high, as recalled by Rumi’s verse,

modern “wheat” has been selectively bred to grow to only about 18 inches, so

that its growing season is curtailed and its shorter stalk can bear a greater

yield of kernels without bending or breaking.

As compared with the “stale rags” invoked by Pound’s poetry, this

degraded “wheat” is actually less nourishing.

In fact, it’s positively harmful to health, causing those who ingest it

to ride a roller-coaster of spiking blood sugar and surging insulin that leaves

them constantly hungry and fatigued. And

the stealth substitution of this cheapened grain – not only in breads, pastries

and pastas, but as an inexpensive “filler” in virtually all processed foods –

has triggered an epidemic of diabetes and obesity over the past few decades

that is unparalleled in history.

How could such a crime against humanity, against the human Spirit, and

ultimately against Nature herself, have been carried out in plain view without

massive outrage and condemnation? Not

only was there no indictment of the corporate perpetrators of this atrocity,

but, until quite recently, they were universally lauded for their good deeds in

fighting world hunger (notwithstanding that world hunger has increased

dramatically with the introduction of high yield grains). Is this just another instance of greed run

amok, or of capitalism’s imperative to maximize profit? If so, maybe we just shrug our shoulders and

listen to the advice of the new wave of diet experts, who now urge us to stop

eating wheat products – after preaching for decades the benefits of “healthy

whole grains”.

But the profit motive alone cannot explain this type of phenomenon, in

which enterprises are seemingly willing to sacrifice the long-term viability of

their business for a short-term advantage.

Climate change is another obvious example, with the extractive

industries quite happy to see the planet go to hell-in-a-handbasket so long as

they can squeeze the last drop out of their fossil fuel reserves. Capitalism would not have survived the past

500 years if this had been its inherent dynamic. Something else is at work here, something

that has achieved dominance over Western society relatively recently, within

the past 50 years. I say “something

else”, rather than “something new”, because what we’re seeing now are the effects

of an ancient evil, a cancer that has advanced and receded over the course of

history, but has now entered the terminal stage,

“Short-termism” is a mode of business conduct that characterizes an

overly “financialized” economy, one in which productive activity has become

less rewarding than speculation on the rise and fall of prices, whether it be

of physical assets, securities or currencies.

Since the key to successful speculation is leverage, a speculative

enterprise is much more dependent on debt than a productive one. And so, in plain speaking, we have devolved

into an economy, often referred to as “vulture capitalism”, that incentivizes parasitism. Parasites need not be concerned with the

long-term viability of their hosts; when one dies, they just move on to the

next.

As we shall discuss in further detail in this Chapter, all of this is

an inevitable outgrowth of unrestrained usury, which only emerged in the United

States in the late 1970s. But before we

delve into historical evolution of usury which has brought us to this

calamitous juncture, we first need to understand the particular strain of pathological

consciousness that has coevolved with usury and makes our society an easy prey

for this economic virus. Before a

parasite can successfully infest a host, it must trick the host into accepting

it as if it were part of the host itself.

The horrors that have attended the rise of a usury-dominated economy –

perpetual war, oligarchic tyranny, debt peonage, environmental degradation – could

only have been tolerated by a people who have internalized and identified with the mindset of treachery,

and thus have become powerless to resist it.

Merchants of Time

“Time is money,” is a phrase all of us have repeated many times,

without really thinking much about what it actually means. It only makes sense in a setting where usury

is so deeply ingrained that the capacity of money to grow of its own accord,

simply with the passage of time, is taken totally for granted. In a purely productive context, nobody pays

you for your time. If you are paid by

the hour, the money flows from the labor you perform in that hour, not from the

time spent. But the accrual of interest depends

only on the passage of time. Does the

usurer perform any useful work for you while the clock ticks away the interest

on your loan? “He foregoes the use of

his money for that duration,” you might naively answer, perhaps unaware the

usurer can re-lend the dollar he lends you at least ten times over, and so

foregoes nothing.

The philosopher Seneca, Nero’s mentor whom we encountered in our last

Chapter, once observed that usury is the sale of time, which belongs to no

one. As a usurer himself, Seneca

recognized that usury requires a particular type of temporal consciousness –

one which regards clock time as something quasi-tangible, capable of being

bought and sold, instead of as simply abstract units of temporal measurement. This kind of thinking, called “reification”,

involves assigning reality to things that are not real. It extends to usury itself, in which money is

seen as a valuable commodity, instead of a mere measure of value. My reader may recall our discussion in

Chapter Three of the Qlippot, the sub-real

Vanities that can emerge from the inchoate shadows only if reified by a deluded

consciousness. Such reified Vanities

form the mental “static” which obscures the sparks of supernal Light scattered

through our World.

In the case of clock time, the process of reification involves

“spatialization”. Perhaps the simplest

example of temporal spatialization is a “timeline” – familiar to devotees of

“Facebook” – in which events are displayed in a spatial sequence extending from

the more distant past to the present.

Within our own minds, we conceptualize our lives as a linear succession

of years spread out in an interior “mind-space” from our birth in the past to

our death in the future. But these

spatial narratives of clock time are purely metaphorical, because no one

directly experiences time in this mode.

We perceive neither the past nor the future, only present moments,

one-by-one, which appear to be connected and continuous with one another only

because our temporal perception is itself intermittent, as evidenced by our

illusion that the rapidly blinking lights on a video screen form an unbroken

progression of scenes.[1]

So our temporal consciousness is “disjunct”, as Ezra Pound aptly

expressed it, having no unifying thread, just an “overblotted series of

intermittences”.[2] Not only is the spatialized time that unfolds

in our inner mind-space unreal, but it’s full of gaps, as the familiar Paul

Simon lyric observes:

Half of the time we’re gone, but we don’t know

where, we don’t know where…

How in the world could such a radically flawed consciousness have

developed in human beings? Could be the

Darwinian genie who assures the “survival of the fittest” was asleep on this

one? Our awareness of the defects in our

own consciousness is, of course, always obscured by the fact that we are

looking into a mirror that is warped by those very same defects. That’s why all the great spiritual teachers of

our race have had to resort to parables and allegories, so that we seem to be

looking at someone or something else, and not into our own deformed souls. Following their example, then, let’s attempt

an allegory of our own to better understand why our perception is intermittent.

Imagine a pair of Siamese twins, who are composite beings without

separate and distinct bodies. Since

their torsos are interconnected at various junctures, surgical separation of

the twins necessarily creates gaps, which must later be repaired or augmented

to approximate a complete human anatomy.

We can even extend this scenario to Siamese triplets, quadruplets, etc., until we imagine an entire

population of congenitally interconnected people, who are ripped apart but not

repaired, so that the disfiguring breaches remain. Like amputees, they often feel as if the

severed members are still there, still part of themselves.

Turning now from allegory to reality, we are those disfigured insular beings of our parable, with our

erstwhile internal connections to a higher Collective Consciousness ripped

away, leaving the telltale wounds still gaping for all to see – all, that is,

but ourselves.

Alas, the time is coming when man will no

longer give birth to a star. Alas, the time of the most despicable man is

coming, he that is no longer able to despise himself. Behold, I show you the

last man.

'What is love? What is creation? What is

longing? What is a star?' thus asks the last man, and blinks.

The earth has become small, and on it

hops the last man, who makes everything small. His race is as ineradicable as

the flea; the last man lives longest.

'We have invented happiness,' say the

last men, and they blink.[3]

Quite evidently, we are the

“last men”, and Nietzsche’s brilliant prose finds the perfect image for our

disjunctive, intermittent perception, the sad legacy of the dissociation of our

Higher Being. The word “blink” derives

from the Middle English, blenchen,

which denotes deception, much as we instinctively “wink” to signal that we are

putting one over on someone. Philosopher

Martin Heidegger eloquently expands on Nietzsche’s insight:

… To blink – that

means to play up and set up a glittering deception, which is then agreed upon

as true and valid – with the mutual tacit understanding not to question the

setup. Blinking: the mutual setup, agreed upon and, in the

end, no longer in need of explicit agreement, of the objective and static

surfaces and foreground facets of all things as alone valid and valuable – a

setup with whose help man carries on and degrades everything.[4]

Ezra Pound picks up on the same theme in the first of his “Pisan

Cantos”, so named because they were written in an American military prison camp

in Pisa, Italy, where the 60-year-old poet was held in a 6-by-6 foot cage,

exposed to the elements, in the waning days of the Second World War. Echoing St. John of the Cross, Pound speaks

of the Night of the Soul, in sense of the Anima,

the Collective Soul of all Beings, and deplores the broken spezzato state of our perception.

Zarathustra, now

fallen out of use…

under the olives

timeless Athene

little owl with glittering eyes…

that which gleams and

then does not gleam

as the leaf turns in

the air…[5]

The owl-eyed goddess Athena represents the fallen Anima, consigned to the dark underside of our insular personae,

like the dark underside of the leaves of her sacred olive tree. Since olive oil was the principal fuel of ancient

Greek lamps, the owl-like blinking of the tree and its goddess signifies a

broken Light, interrupted by shadowy intervals.

And what is it which lurks in these shadows, dismissed by the “last man”

as useless, like the words of Zarathustra?

Pound gives us a hint by naming this particular Canto Nekuia, after the title of Book XI of

the Odyssey, in which the hero visits

the Land of the Dead.

Not only is our temporal perception discontinuous, it’s also

asymmetrical, progressing only forward through time, and leaving a seemingly

immutable past in its wake. We might

infer from this that the asymmetry somehow causes the discontinuity, and that,

if we were able to reverse gears and go backward, into the Past, into the Land

of the Dead, we would find there the missing pieces of our decimated Soul. It’s noteworthy that Nietzsche himself saw

the primary obstacle standing in the way of the diminished “last man” crossing

the bridge to the consummate humanity of the Higher Man as lying in the

ostensibly frozen Past, impenetrable by the human Will. Under his reckoning, Falsehood does not need

to be negated, because it does not have an affirmative existence of its own,

but constitutes only the incompleteness of Truth.

A Spirit who has

become free stands… in the belief that only the partial is loathsome, that all

is redeemed and affirmed in the whole – he does not negate any more.[6]

On this point, Pound joins Nietzsche in disavowing Negation and in

proclaiming the glow numen of ecstasy

arising from unabridged perception.[7] And the words of Zarathustra pronounce the

same theme – that the possession of complete Selfhood seeks to eternalize all

things:

All things are

entangled, entwined, enamored… You higher men, learn this: Joy wants eternity. Joy wants the eternity of

all things, wants deep, wants deep eternity![8]

What is it, then, that prevents us from embracing this unbridled joy,

this numinous ecstasy? Something has

crept into the fissures of our fragmented Soul, into the delusional mind-space

of our spatialized time. It belongs to

the realm of the Vanities, the Qlippot

wreckage of abortive worlds that never attained full Reality. William Blake calls this spirit of Negation the

“Spectre”:

The Negation is the

Spectre…

This is a false Body,

an Incrustation over my Immortal

Spirit; a Selfhood,

which must be put off & annihilated always

To cleanse the Face of

my Spirit by Self-Examination.

…To cast off the idiot

Questioner who is always questioning,

But never capable of

answering…[9]

As we shall see, it is this Specter which constantly robs us of our

full, ecstatic perception of the eternal Now and separates us from our higher

Selfhood. The Specter does this by

warping the mind-space it inhabits to make the inner strata of our persona,

which connect us to our fellow Beings, appear remote and inaccessible, like a

distant Circumference.

For the Sanctuary of

Eden is in the Camp: in the Outline,

In the Circumference:

& every Minute Particular is Holy:

Embraces are

Cominglings: from the Head even to the Feet;

…What is Above is

Within, for everything in Eternity is translucent:

The Circumference is

Within: Without, is formed the Selfish Center

And the Circumference

still expands, going forward to Eternity.

And the Center has

Eternal States! these States we now

explore.[10]

The Circumferential Circus

A circumference defines the outline of a circle, and so is associated

with the numinous Mandala symbols that form the bedrock of what we now call our

Collective Unconscious, but is

actually the submerged remnant of what once was a Universal Consciousness. Represented in the Tarot by the trump

entitled “The World” – which translates as Olam

in Hebrew – the Circumference connotes completion and integration, particularly

with reference to the Selfhood. Since it

is the last of the Tarot trumps, “The World” also has apocalyptic associations,

as evidenced by the presence of the Four Beasts of Revelation 4:7 around the

central Mandala, and further suggested by its number 21, which expands to 777 –

the gematria of “World of the Qlippot” (Olam haQlippot).

As a symbol of the human Persona, the Circumference stands in relation

to the circle’s Center, which Blake styles the “Selfish Center”, with self-ish being something of a double

entendre. While our “selfish” insular

ego-self corresponds to the one-dimensional point at the center of the circle,

invisible radii link it to every one of an infinite number of points on the

Circumference, as we recall from the words of Dante’s angelic interlocutor:

I am the center of a

circle which possesses all parts of its circumference equally, but thou not so.[11]

Clearly, Dante’s angel represents his Higher Self, his complete,

integrated Persona, which is capable of direct discourse with God. But if this Higher Self is at the Center, in

what sense does it “possess” all of the countless points on the Circumference? And who or what are these circumferential

points?

For the answers to these questions, we must follow Dante’s example and

enter the Underworld, where the Past is still present and the Dead are alive. Dante’s modern counterpart, Ezra Pound, did

precisely that as his own formidable persona disintegrated under his brutal

imprisonment at Pisa, where he was caged like an animal in an open-air “death

cell”. As his sense of who he was began

to slip away – this greatest of American poets, scourged and vilified by his

own countrymen for speaking out against the usurers and their endless wars – he

at last had his moment of revelation and redemption. In the birds which came and went, perching on

the wires of his cage, Pound envisioned a musical score, with the birds as

notes and wires as the staff lines.

Out of Phlegethon!

Out

of Phlegethon,…

art

thou come forth out of Phlegethon?...

–

not of one bird but of many[12]

What Pound was actually experiencing, rather than merely

intellectualizing, was his Selfhood not as a single state of Being, but rather

as a composition of multiple states – “not of one bird, but of many” – each of

which has value and meaning only in the context of the composition as a whole. It is this integral Persona that rises,

Phoenix-like out of Phlegethon, Dante’s infernal River of Fire, which surrounds

the Seventh Circle of the Usurers and represents the mental prison of

spatialized linear time.

When we discussed, in Chapter Three, the process of quantum

decoherence, which results in an continual splintering of our reality into

“many worlds”, we decided, for the time being, to defer the question of why we

don’t experience these “other worlds”, inhabited by other versions of

ourselves. We are now ready to address

that question, in light of a multifarious Selfhood constituting the

Circumference of which Dante’s angel spoke.

As the angel observed, we “last men” are not in possession of that

Circumference, due to our disjointed mode of perception, dominated by the

Specter. Yet we have within us, in a

repository unreachable by the Specter, a continuous locus of Immaculate Light,

which is the Soul or Anima. Our “guardian angel”, the Anima retains its connection to the circumferential

Higher Self, through its “bridge over worlds” in Pound’s imagery, even though

our diminished personae can no longer access that bridge. We recall the verses of Guido Cavalcante

extolling the Anima:

… Willing man look

into that formed trace in his mind…

Itself moveth not,

drawing all to its stillness,

… nor is it to be

known from its semblance,

But, taken in the

white Light that is Allness,

Toucheth its aim,

… led by its own emanation.[13]

As Pound notes in his Cantos,

Guido Cavalcante’s poetry was influenced by the writings of 11th

Century St. Anselm, who identified the feminine Anima with the Third Person of the Holy Trinity. She is the incorruptible Essence of all

created Beings, which we have encountered before as the Pure State or Apeiron, in which all things

cohere. Because the Anima exists “not in space, but in knowing”,[14]

She is in untouchable by the Specter, which is confined to the virtual realm of

spatialized time.

All of these connections were doubtless not lost on Il Maestro, the immortal film director

Federico Fellini, when he chose the name Guido Anselmi for his alter-ego

character (played by Marcello Mastroianni) in his masterpiece 8½.

Unable to create anything new, filmmaker Guido is dogged by the scornful

questioning of a cynical film critic (his Specter) and paralyzed by a seemingly

immutable past, in which the failures, lies and betrayals of his relationships

with his producer, wife and mistress are all locked in, like scenes of a movie

he has already shot. Fellini’s alter-ego

is haunted throughout the movie by apparitions of his dead father and mother,

and he’s transported in his dreams to a stark mortuary, where he seeks their

solace. In one of the film’s early

scenes, a night-club mind-reader probes Guido’s thoughts, pronouncing the words

Asa Nisi Masa – a rendering of Anima in a kind of pig-Latin code Guido

had learned while a child as a magic spell to conjure ghosts from ancestral portraits

hanging in his home.

His desperate search for the Anima,

for the Muse in the form of a living woman, takes him through an agonizing

marathon of screen tests of lovely actresses, but the past keeps constraining

him to mold his leading ladies in the images of either his wife or his mistress,

much to the consternation and humiliation of both of them. Suffocating in his own mental prison without

inspiration, what little is left of Guido’s artistic vision can only beget an

absurd image of his pathetic wish for escape, in the form an enormous spaceship

set he has built in the middle of nowhere.

Finally, with nothing even approaching a script and forced by his

producer to attend a raucous, mortifying press conference at the spaceship

site, Guido’s persona breaks down, and he pitifully crawls beneath the press

table to shoot himself.

Yet, inexplicably, we see Guido (or perhaps his wraith?) in the next

scene unscathed, though totally deflated, being led by his film critic Specter

away from the movie set, now being demolished.

While his Specter is urging him to abandon his creative work and resign

himself to silence, he is approached by a former cast member who tells him,

“We’re ready to begin.” Returning to the

set, Guido finds himself in the center of a large circus ring, with all of the

characters he had encountered or imagined during the course of the movie taking

their places, at his direction, along the circumference of the ring. As Guido goes out to the ring to join them,

they all begin to dance around the circumference to a jaunty carnival tune

played by a troupe of clowns.

Perhaps the most poignant dialog in the incredible finale of 8½ are the words of Guido’s misused

mistress as she takes her position in his circumferential circus. Instantly shedding all the emotional pain he

has inflicted on her, she exudes: “Now I

understand what you meant all along: You can’t do without us!”

[Above, a photograph

of Alexander Calder’s “Circus”, displayed at the Whitney Museum]

I have gone to the trouble of synopsizing this movie, which I know

many of my readers have seen, because it’s such a wonderful parable explaining

who we really are and what our lives are really about. In the end, Guido’s redemption lies in his

possession of every point on the Circumference of his Being, his embracing of

every person in his life, every character in his films, as an essential part of

his own Persona, so that in his immortal Selfhood they are all entwined

together as One. By daring to step out

of our little ego-selves, out/in to the Circumference of our alternate avatars,

and inhabiting these alternate versions of ourselves, we give those avatars

Life, and in so doing, find our own true Life in the Higher Self which we

create. Ezra Pound said it more

poetically, though perhaps not as vividly as Fellini.

The ‘magic moment’ of metamorphosis, bust

thru from quotidian into ‘divine or permanent world.’[15]

The erection of microcosmos consists in discriminating these other

powers and in holding them in orderly arrangement about one’s own.[16]

Not all of us are artists or poets, but all of us are creators,

because we have within us – in the form of the Anima – the Divine Image, the Image of the Universal Creator, the

omniscient Knower, as St. Anselm conceived Her.

We are on this Earth to build something, something unique to our own

particular Soul. Again, Pound saw it

with such clarity:

The soul of each man

is compounded of all the elements of the cosmos of souls, but in each soul

there is some one element which predominates, which is in some peculiar and

intense way the quality or virtue of the individual; in no two souls is this

the same.[17]

… and the soul’s

job?... To build light…[18]

We fulfill our sacred obligation to build Light under the guidance of

our feminine Anima, who was

personified as Beatrice in Dante’s Divine

Comedy. But, due to the profound

degeneration of human Consciousness that has occurred from Dante’s time, which

was free of usury, to our own, which is dominated by it, She has withdrawn from

our thoughts, from the mind-space inhabited by our Specter. Consequently, we must pursue our task by

trial-and-error, in a process that mirrors the Catharsis of Error in the

macrocosm. As I explained in my book

previous to this one,[19]

the laws of quantum physics dictate that everything which can possibly happen

actually does happen in one or more

of the infinite number of universes that make up the Multiverse. Each of the photons that are travelling from

this page into your eye is actually traversing not one path, but many, both

forward and backward in time, along the way transforming itself into other

types of particles and back again before striking your retina. The multiple paths that the photon travels

can be depicted in something called a “Feynman diagram”, named for theoretical

physicist Richard Feynman, one of humanity’s true intellectual titans. In the upshot, only one photon path manifests

itself, but that path is actually a summation or integration of all of the alternative

paths.

So in the quantum macrocosm, most of what pops into existence pops

back out without becoming part of our experience, without ever having a

Presence in Being. But it doesn’t

disappear without a “trace”, and that “trace” is what physics calls the “vacuum

energy”, the source of the Vanities or Qlippot. Although the Vanities are not Real, they can

be “reified”, or perceived as real, by a false consciousness, such as that of

spatialized time engendered by usury.

Hence the process of erecting the microcosm of the immortal Higher Man

involves the same Catharsis of Error that proceeds in the macrocosm of the

Multiverse. Like Feynman’s photon, we

must tred the paths of all of our avatars, all of our alternate selves, some of

whom appear as “others” in this life, some of whom have already passed on from

this world, and some of whom are yet to be born. To do this, we must be able to move both back

and forward in time – a process which Pound describes as the “Periplum”.

“the great periplum

brings the stars to our shore”… goes the thought, time turns back…[20]

The forma… the dynamic

form which is like the rose pattern driven into the dead iron-filings by the

magnet… Thus the forma, the concept rises from death.[21]

Hast ‘ou seen the rose

in the steel dust?

… so ordered the dark

petals of iron

we who have passed

over Lethe.[22]

By navigating the alternative paths of the Periplum, we filter out the

mental static that fills the voids between the scattered points of Light, and

thereby “bring the stars to our shore”. In the course of this Periplum navigation, our

Consciousness goes backward as well as forward in time in order to trace the

“unseen form” of the Anima, the

gateway to our Higher Self. That divine forma effaces the barriers between

living and dead, animate and inanimate, infusing all with the pattern of Life,

like the magnetism that arranges iron filings in the shape of a rose. As we move back-and-forth across the

now-passable boundary of the Past, to bring it into Presence and restore its

Being, we find ourselves crossing over the mythical River Lethe, in which

Memory is purged of Falsehood. Thus does

the Catharsis of Error extend Feynman’s “sum over paths” to a “sum over worlds”,

so that the divergent paths/worlds of error cancel one another out.

And so the perfect form of the Anima

“rises from death”, like the sublime Goddess of Love emerging from the

waves of the sea. But this numinous

emergence cannot occur within the turning wheel of spatialized clock time, but

only in the eternally present Now – what the poet Robert Graves calls the

“still, spokeless wheel” of Persephone.[23] In this ethereal stillness, the noise of the

clashing Vanities ceases, and the music of eternal Verity becomes audible.

… and saw the waves

taking form as crystal,

notes as facets of air,

and the mind there, before them, moving,

so that notes need not move.[24]

Itself moveth not,

drawing all to its stillness…[25]

Unless we “bust through from quotidian… into permanent world”, as

Pound urges, we are captives on the Wheel of Fortune, ruled by random chance,

which is the only law followed by the Vanities.

But if we shift the focus of our perception into the present Moment, the

Wheel stops turning, and the random outcomes offset each other, leaving what

Pound envisions as a “path as wide as a hair”.

You who dare

Persephone’s threshold,…

to enter the presence

at sunrise

up out of hell, from

the labyrinth

the path wide as a hair…[26]

Pound’s imagery was likely influenced by St. Paul’s legendary vision

of the Third Heaven, which he reached by traversing “over a turbid river…a

bridge as fine as a hair, connecting this world with Paradise”.[27] In the fragmentary notes at the end of his Cantos, Pound describes a similar vision

of butterflies – a traditional symbol of the Soul – flying toward a “bridge

over worlds”,[28]

which connects with the “sum over worlds” resulting from the Catharsis of

Error.

By constant

elimination

The manifest universe

Yielded an armour

Against consternation,

A Minoan undulation,…

Strengthened him

against

The discouraging

doctrine of chances…[29]

As we discussed in Chapter Three, the mythical thread which leads us

out of the hellish labyrinth of spatialized time is supplied by Ariadne, whose name means “Most Holy” in

Cretan Greek. After following her thread

to escape the deadly Labyrinth of her father, King Minos, Theseus abandons

Ariadne on the island of Naxos, where she is saved by the god Dionysus and

becomes his bride. Dionysus, like

Persephone, is one of the deities who crosses the border between Life and Death

and integrates the Past with the present Moment. He presides over the Lesser Mysteries of

Eleusis, which aim to reverse the decoherence of clock-time and restore the

Pure State, or Apeiron. By enacting Pound’s “Minoan undulation”

back-and-forth in time, Dionysus undergoes a continuous process of creative

Self-transformation, a regenerative Metamorphosis which draws upon a multitude

of background avatars to infuse each instant of experience with improvised novelty

and vital energy.

void air taking pelt,

Lifeless air become

sinewed,…[30]

And so the Dionysian formula for liberation from the labyrinthine

strait-jacket of spatialized time is the continuous renewal of an eternal

Present, in which the entire cosmos is alive and aglow with numinous fire – a

fire that consumes the dross of the random Vanities. Upon choosing to wed Ariadne, Dionysus places

on her head a crown that is translated into the heavens in the form of the

constellation now known as Coma Berenice,

but originally called “Ariadne’s Hair”. Styled

the “Heavenly Circuit” by Yeats,[31]

the constellation is yet another manifestation of the archetype of the “still,

spokeless wheel” of the Collective Soul Anima,

which integrates the divergent paths of the “many worlds” into one golden

thread, one “bridge over worlds”, rendering perception perfectly coherent and

paradisiacal.

But if the integration of Ariadne’s thread does not take place, the

ever-branching paths of the quantum universe are chaotically superimposed to

form a prison for the persona, like Pound’s Pisan “death cell”. Like the maze of King Minos, this one harbors

a monstrous, inhuman creature, the personification of the Vanities.

That Man be separate

from Man,…

… the Law of God who

dwells in Chaos,

hidden from the human

sight…

… an endless labyrinth

of woe!

…So spoke the Spectre…

… Worshiped as God

by the Mighty Ones of

the Earth[32]

A Private Universe

The degraded culture of unrestrained usury breeds a warped mode of

perception which reifies clock-time and spatializes it, so as to impose a rent

– known as interest – on the use of this metaphorical “space”. But this “space”, lacking true Reality, is a

barren landscape, a vast Wasteland that expands, cancer-like, at the

exponential rate of compound interest.

The wasteland

grows. Woe to him who harbors wastelands

within![33]

The “wasteland within” each of us is like a private stage, in which we

are the only audience. On that stage

performs an analog version of our self, an alter-ego of sorts, who constantly re-enacts

events of the past, anticipates experiences yet to come, and rehearses

countless illusory scenarios. Not only

does this “actor” continually divert our attention from perception of what is

actually Present before us, but he/she effectively preempts much of our

experience with anticipatory simulations.

This spectral self also writes his/her own script, a narrative of who we

are, what motivates us, our purpose in life.

Experiences that are inconsistent with the script are assiduously edited

or “corrected” by mental reenactment.

Consequently, as the inner Wasteland grows and the spectral narrative

develops over the course of a person’s life, it becomes increasingly uncoupled

from experience, such that experience is drained of immediacy, to which the

narrator reacts with fear. The fear of

exposure – of the narrative being exposed as a sham – haunts and ultimately

paralyzes experience. In a very

Procrustean process, the parts of the Self that do not fit the story-line are

lopped off and jettisoned into the Unconscious.

It’s as if large slices of our lives have gone missing, and the missing

slices make it all the more difficult to formulate a narrative that makes any

sense at all. Small wonder, then, that

life is effectively perceived as meaningless by the vast majority of people.

All of which serves the purposes of the usurers quite nicely, since

people whose inner worlds are empty have a terrible hunger to consume “things”

to fill the void. Pope Francis addresses

this phenomenon in his encyclical letter “On the Care of Our Common Home”:

When people become

self-centered and self-enclosed, their greed increases. The emptier a person’s heart is, the more he

or she needs things to buy, own and consume.

It becomes almost impossible to accept the limits imposed by

reality. In this horizon, a genuine

sense of the common good also disappears.[34]

Truly, the Specter within each of us literally howls with a hunger

that can never be appeased. Even the

ego-self has limits on its appetites imposed by its interactions with the real

world, but on the private stage of our spectral self, such barriers can simply

be swept away. In the airless incubator

of our insular mind-space breeds a pathogen of spectacular virulence.

Woe to you who add

house to house and join field to field, until no space is left, and you live

alone in the land.[35]

Martin Luther equates this usurious mind-set with the legendary

monster Cacus, “who would have the whole world perish so that he may have all to

himself”. It goes beyond greed and

avarice to an unbridled lust to possess everything, an accursed compulsion for

aggrandizement, known as pleonexia,

which negates all Being but one’s own. In

a society dominated by usury, pleonexia inevitably becomes the ruling ethic,

and “civilization” is nothing more than a thin veneer over a bestial war of

“all against all”.

Such unabashed idolatry of wealth excludes the possibility of genuine

Love, genuine empathy with any other person.

The Specter views all others as posing an inherent threat to his/her

absolute right to have everything and be everything. And so, all “others”, even those ostensibly

closest to us, are objects of hatred by our phantom self, who increasingly

inhabits a world of his/her own, a private universe where he/she need never be

bothered by the feelings and needs of others.

Of course, for the modern CEO, such a private universe is merely a

logical extension of his/her private yacht, private jet, private villa, private

island – though he/she might also need his/her own private spaceship to go

there, as Fellini’s alter-ego was preparing to do in 8½. Thus does the usurer

embrace the mental state of the Fallen Angels.

The Hell within him, for within him Hell

He brings, and round about him, nor from Hell

One step no more than from himself, can fly

By change of place…

… which way shall I fly?...

Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell;[36]

Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscrib'd

In one

self-place; but where we are is hell,

And where hell is, there must we ever be.[37]

Ultimately, our internal world of spatialized time devolves into a

solipsistic universe, in which the Specter is the sole inhabitant. The Specter constantly tempts us with images

of its version of “paradise”, in which every selfish wish of ours is granted

and we have everything we want. Only the

divine Mercy of God keeps this vile Genie in its bottle, for if we could indeed

realize our every wish, we would find ourselves alone in an empty world,

designed exclusively for us and no one else.

But the one wish the Genie cannot grant us is immortality, because the

time-line of its mind-space must have a terminus, where the narrative ends,

beyond which is an absolute Void, which Blake calls Ulro.

As the Specter obsessively peers into this Abyss of Non-Entity, it

reacts with a suicidal despair. Since

its solipsistic universe can have no meaning without its only resident, the

looming Void at the end of spatialized time is a consummate undoing that

renders everything else pointless. Death

becomes categorically unthinkable – unless it is the Death of Everything, the

End of the World, in which the Specter goes down in a glorious Gotterdammerung of universal

conflagration.

Consequently, to the extent that our ego-self is drawn into the

labyrinthine web of spatialized time woven by usurious consciousness, it

increasingly identifies with the Specter and sees the end of its being – and

ultimately all Being – as necessarily coincident with the termination of the

phantom self and the insular mind-space it inhabits. Of course, the actual Reality is quite

different: the self-enclosed world of the Specter in fact shuts us off from an

infinite Interior, which we share with everything else in the Multiverse, and

in which there is no Death, only eternal Being.

So the Specter’s demise is in fact our Resurrection, the Resurrection of

the Body, freed at last from the hypnotic spell of the disembodied analog self.

All of this explains why our society is haunted by a collective

death-wish. The teachings of humanity’s

prophets, which envision the end of spatialized time as a liberating Jubilee,

have been perverted into a narrative of inevitable doom – a doom that mankind

is rushing to embrace. Beginning in the

20th Century, when the stranglehold of usury over Western

civilization began to tighten, the prospect of species suicide, theretofore

unthinkable, became an everyday contingency.

And now, of course, in the 21st Century, we have progressed

beyond that into an impending planetary suicide. A sixth, and perhaps final, Great Extinction

is now officially underway, with Man’s reign over the Earth seemingly about to

culminate in the most total annihilation that Nature has ever endured.

And yet, with this fathomless precipice looming before us, we continue

to “go about our business”, which is the business of “letting our money work

for us”. But something has to be alive

to work, doesn’t it? Led by our deluded

mind-space narrative, we are eradicating Life so that we may animate

lifelessness. Tied to a dying Specter,

we have personified wealth itself, granted it a corporate personhood, and made

it immortal – what’s more, made it our god.

Unless we awake from our collective trance very soon, we are about to

follow this infernal god down into the deepest pit of Hell.

At this point, I can almost sense my reader squirming in his/her

seat. I have been speaking a bit too

directly, without the soothing deflection of parable. Looking into the mirror, none of us see a

Specter lurking there. We see a face; we

answer to a name. But we are not that

face; we are not that name. We are part

of a higher Being, spanning the many Worlds of the Multiverse, who has

countless faces and whose only Name is “I AM”. The face in the mirror (or, to be more

contemporary, the “selfie” photo) and the name we call ourself are part and

parcel of the “static” which diverts us from who we truly are. They are the primary hooks by which the

Vanities attach themselves to us and obscure the wellsprings of our eternal

Life. Better that we cast our mirrors

and “selfies” into a bonfire, as did the 15th Century Florentines at the urging of saintly Savonarola, and

instead, recollecting the poetry of Cavalcante, look inwardly at the “formed

trace” that is not “known from its semblance”.

All these people that

you mention, yes I know them, they are quite lame.

I had to rearrange

their faces and give them all another name.[38]

If my skeptical reader will indulge me, let’s attempt an experiment

together. Let us attempt to experience

the Present moment, and nothing else.

Sounds like a simple task, doesn’t it?

But something keeps getting in the way.

Images pop in and out of our minds, like the ephemeral Vanities that

inspire them. We see “ourselves” doing

things we have planned for later in the day, or tomorrow, or next week. We see “ourselves” re-living some event from

our past. We see “ourselves” having a

conversation with someone that has never occurred and probably will never

occur. If the imagined conversation is

heated, our pulse will quicken as if it were real. These spectral doings of “ourselves” can fill

us with fear or joy or remorse or shame which mimics, and often takes the place

of, actual experience.

What we see as “ourselves” in this experiment is what I’ve been

calling the “analog self” or Specter. It

operates to take us out of the Present moment as often as it can, because

prolonged engagement with the Now can awaken the Anima and open her Gate into

the realm of the Higher Self, beside which the Specter will disperse like a

cloud of smoke in a brisk wind. Without

the interior “stage” of spatialized time and its narrative script, the analog

self slips back into the sub-reality of the Qlippot. We know that the Qlippot cannot rise to the

level of manifest existence on their own, but instead need to be energized by a

false consciousness that accords them the reality they lack. As you might guess, the Specter in each of us

is the key agent of that energy transfer – an energy transfer that depends upon

our acquiescence to a passive mode of perception, in which we are absent from

the Now most of the time.

God’s eye art ’ou, do not surrender perception.[39]

A common symbol of spatialized time is a river, with the metaphor of

extension in space expanded into movement through space. Since the river bears us along, willy-nilly,

we are not actively involved in where it’s taking us, but are merely “along for

the ride”. Our experiences are largely

determined by Chance, which is the operative law of the Qlippot. In fact, a society based on spatialized time

invariably enshrines Chance as a sort of deity and develops a cult of

“risk-taking” as the most socially useful activity. Active perception, on the other hand, is

directed by the Will, which moves the Mind.

Since the conveyor of spatialized time will not accommodate a mental

velocity, active perception must step off the conveyor – “bust out of

quotidian”, in Pound’s words – into the “timeless Time” of the Olam.

The Fabric of Reality

Active perception does not passively encounter Reality, it creates

it. It improvises Reality from moment

to moment, in a back-and-forth pattern of involution and evolution which may be

likened to the movement of a weaver’s shuttle back-and-forth across a

loom. Goethe’s imagery of this process

is especially vivid:

Truly the fabric of

mental fleece

Resembles a weaver's masterpiece,

Where a thousand threads one treadle throws,

Where fly the shuttles hither and thither.

Unseen the threads are knit together.

And an infinite combination grows.[40]

Missing from passive, spatialized consciousness is the backward

movement of the shuttle, the inward-moving phase that is the source of all

novelty and spontaneity. While the

mind-space engenders a spectral vivification of lifeless abstractions, such as

money and time, the moving Mind of active perception re-animates the palpable

threads of sensation, weaving them together so that the “gaps” of intermittent

perception are closed and a continuous locus of experience is formed.

So they stood in the

gateway of the fair-tressed goddess, and within they heard Circe singing with

sweet voice, as she went to and fro before a great imperishable web, such as is

the handiwork of goddesses, finely-woven and beautiful, and glorious.[41]

Usura… gnaweth the

thread in the loom

None learneth to weave

gold in her pattern;[42]

In the “imperishable web” of active perception, everything is alive,

everything has a voice, and all voices together join in a magnificent angelic

chorus. Like the “bird-on-a-wire” notes

of Pound’s captivity, the fabric of Reality is animated by an improvising Mind,

which overleaps the voids of dead “static” to bring all branches of experience

back into one common phase. Unlike

passive perception, which is inherently blinkered to all but one branch of the

Multiverse, active perception can skip between the branches, like a melody dancing

from note to note. Unlike the

spatialized time-lines of the analog self, the realm of the moving Mind has no

boundaries, no end-points, no Voids of Non-Entity, no Death, no Hell.

To live a thousand

years in a wink…

Nor begins nor ends

anything.[43]

With splendor,…

Woven in order,

As chords in the loom[44]

…the Divine Mind is

abundant

unceasing

improvising

Omniform

unstill[45]

And so, every moment that is fully perceived forms a Presence in

Eternity, a Presence which spontaneously metamorphoses, like Dionysus,

improvising a scintillating tapestry of omniform sentience.

If the divine tapestry is our metaphor for active perception, however,

the chessboard must serve as the contrasting metaphor of passive mind-space

experience. (No disparagement of the

game of chess itself is intended here; indeed, chess-playing is an excellent

exercise in mental agility.) The

chessboard can be viewed as a spatial-temporal grid, like that associated with

Cartesian axes, in which one axis represents spatialized time and the other a

direction in actual space. A graph of

the vertical path of a projectile over time is one example. But the chessboard adds another interesting

feature by making the squares of the grid alternate in color, black and

white.

Whenever the opportunity presents itself, I like to tour Masonic

lodges, since the Freemasons are heirs to the legacy of the Knights Templar,

who revived usury after its long ban during the Middle Ages. The Masons continue to use Templar symbolism,

such as the chessboard pattern, though they are mostly ignorant of its occult

content, except perhaps at the highest levels of their Craft. At any rate, while touring the Masonic Temple

in Philadelphia on one occasion, I asked the guide why many of the floors had

chess-type tessellation. “It represents

good and evil,” was his response, which was, like all falsehoods, merely an

incomplete truth. The Masonic chessboard

does indeed relate to the Tree of Good and Evil, the Tree of Dualism, of which

Freemasonry is one variety. But it also

relates to the process of temporal decoherence that blocks our return path to

the unitary Tree of Life – a blockage represented by occultist Crowley’s

Flaming Sword, as we discussed in Chapter Three.

Interestingly, the chessboard paradigm of spatialized time plays a

central role in an allegory written by a German economist Michael Flürscheim around

the turn of the 20th Century as a warning that the mathematics of

compound interest preordains that all wealth will ultimately be sucked into

usury’s black hole.[46] The tale begins some ages after Man’s

expulsion from Eden, with a merciful God dispatching one of His Angels, the

Spirit of Invention, to lighten mankind’s toil.

After the Promethean Angel had taught humanity the use of steam power,

electricity and machinery, the resulting explosion of productive wealth seemed

poised to lift humanity back into Paradise.

But Satan, fearing the imminent loss of his Empire, called upon one of

his minions, the Demon Compound Interest, to undo the benefits of

technology. “Instead of their being a

source of blessing to mankind, I shall make them the producers of untold misery

– worse than ever man suffered from thy hands,” he assured his master.

And so the battle was joined on a great chessboard. Against the myriad forces of mankind’s

angelic benefactor, the Demon deployed only a single soldier, but with the

stipulation that his army would double with each square on the chessboard

advanced. The Angel agreed, confident of

his victory over the Demon, but by the time the 30th square was

reached, the Demon’s army had swelled to over a billion troops, and the Spirit

of Invention was compelled to capitulate.

Flürscheim’s allegory underscores a critical turning point in the

advance of usury and the temporal mind-set it imposes. When usury spatializes time, in order to

impose a rent on its use, it initially does so in a linear fashion, meaning

that a certain duration in time is always translated into the same extension in

space and bears the same amount of interest.

With the advent of compound interest, however, time was spatialized

geometrically, so that money could grow exponentially, the way the Demon’s

armies did in the allegory.[47] What this amounts to is compressing more

“space” into each passing interval of time, thereby speeding up the temporal

“conveyor” of passive perception, sort of like the runaway assembly line in

Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times.

While natural and social systems have evolved to deal with linear

change, sustained exponential growth must exceed their capacity to adapt. An example often cited is the growth of water

lilies on a pond. If it takes 30 days

for the lilies to cover the pond, thereby killing off everything else, what would

be the right time to cut them back? A

common sense answer might be to wait until the pond is half covered. But if the growth is exponential, that would

actually occur on the 29th day – too late to save the pond life from

annihilation. Obviously, we can apply

this same paradigm to climate change, the effects of which will multiply at an

accelerating rate in the coming years, while we are just now waking up to this

threat quite late on the “29th day”.

As seen by the passive perceiver floating along on the “river” of

spatialized time, the sustained exponential growth dictated by compound

interest transforms the river into raging rapids, in which the genuine

experience of even one moment of peaceful Presence during an entire day, week,

or even month becomes next to impossible.

Thus does the Demon of Compound Interest throw our everyday “rate race”

for survival into overdrive. It’s just

as the Red Queen told Alice:

Now, here, you see, it takes

all the running you can do to keep in the same place. If you want to get

somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that![48]

In the nearly 150 years since Lewis Carroll wrote these words, the

speed-up has continued to the point where running as fast as you can no longer

keeps you in the same place, as the rapidly declining living standards of all

but society’s privileged elite sadly attests.

One unforeseen consequence of time’s geometric spatialization in the

service of compound interest, however, is to progressively squeeze the

mind-space of our analog self. A

traveler of the 19th Century could stand at a crossroads for quite a

long time, while his/her Specter would seem to traverse each of the alternate

paths. But the 21st Century

motorist has a split second to select his/her route, with an electronic

alter-ego barking directions from the GPS navigator all the while. Increasingly, this temporal compression

forces the analog self out of the confines of its private stage into public

view, and this trend is reinforced by the rapid breakdown of personal privacy

under the onslaught of usury’s “tell all” cyber culture and its surveillance

State.

In the upshot, therefore, usury undermines the basis for its own

continued existence, which is the passive consciousness imposed by spatialized

time and its spectral selfhood.

Ultimately, the Specter must appear as a manifest Persona, as it did

briefly in the guise of Nero Caesar, who lasted only a few years after coming

out from his private stage to perform in public. Another avatar of this personification of

Falsehood waits in the wings, but, as was the case with his Roman antecedent,

his exposure preordains his undoing.

Since the Specter is a creature of the Vanities, he – like they – must

ultimately fall short of the threshold of full existence, and his narrative

ends in the Abyss of Non-Entity. Such an

apocalyptic denouement was foreseen by our old friends the Sibyls several

thousand years ago.

Obscurest acts shall

be revealed, his secrets each impart,

So shall God bring all

thought to light, unlocking every heart.[49]

Before we move our shuttle of active perception forward across the

loom into the final Revelation of Falsehood, however, we must draw it back to

weave the threads of the Past into our tapestry of an everlasting Presence. By doing so, we enact the Catharsis of Error,

in which, as Yeats put it, “everything that is not God [is] consumed with

intellectual fire”.

A

Gathering of Vultures

If we draw the shuttle of our loom back to the beginning of Christ’s

ministry, we find him being led by the Holy Spirit into the Wilderness, which

is the archetypal setting of purification in the Scriptures. As I have discussed elsewhere,[50]

the Hebrew gematria of Wilderness Midbar

links it with the complete, integrated human Persona, shaped in accordance with

the Divine prototype. On his way to

assuming the mantle of the Higher Man, however, Jesus is confronted by his own

Specter, who invites him to inhabit a private universe in which he is the

all-powerful ruler, subordinate only to the infernal god of this mind-space.[51] Thus it is revealed that the spatialized time

of the analog self is the source of the idolatry of wealth and power, which the

Messiah is destined to overthrow.

After purging himself of his own Specter, Christ chooses to preach his

first sermon in the synagogue of his hometown of Nazareth. As we might well imagine, the scriptural text

he selected for this occasion speaks volumes regarding his mission on this

Earth. Jesus reads the passage from

Isaiah, Chapter 61, where God’s Anointed One proclaims the Year of Jubilee, in

which the Gospel of the Poor is preached, universal Liberty is decreed, all

prisoners are set free, all debts are forgiven, and the land is restored to its

original owners. As Jesus sets down the

scroll of Isaiah, he announces to the spell-bound congregation, “This day is

this scripture fulfilled in your ears.”[52]

Quite tellingly, the gospel of Luke then goes on to relate how, once

Jesus sits down again, each of the congregants hears the voice of their

spectral self – Blake’s “idiot Questioner” – asking, “Isn’t he only the

carpenter’s son?” And to this day, the

cynical doubts of the Specter within each one of us prevents us from embracing

the Great Jubilee which Jesus proclaimed on that day in Nazareth, and which is

truly mankind’s last remaining hope for survival.

The Jubilee Year, as ordained by Yahweh on Mount Sinai,[53]

reflected a traditional concept of property that is radically different from

that which prevails under the reign of usury.

In this old way of thinking, the rights of an individual in his/her

property are not absolute, but contingent.

We are, at best, stewards of all our possessions in this world.

The land shall not be

sold forever: for the land is mine; for you are strangers and sojourners with

me.[54]

This Stewardship paradigm had persisted in Western civilization until

the later years of the Roman Republic, when the deadly grip of the creditor

oligarchy began to mold the abominable idol of absolute property rights. Before that, however, it was customary in

most societies to observe a periodic “clean slate”, similar to the Jubilee Year

of the Hebrews, in which the burden of debt was lifted off the backs of the

poor, and they were given a fresh start.

Public credit, which was dispensed by government and/or religious

institutions, predominated over private credit until Roman times and enabled

the practice of periodic debt Jubilees.

This practice inhibited the stratification of society based on wealth

and the emergence of a dominant elite of usurers.

But as Rome degenerated from a republic, in which elected Tribunes

protected the common people from the impositions of the large landowners, into

an empire ruled by a creditor oligarchy, the traditions of “clean slates” and

Jubilees were jettisoned. It’s

worthwhile to examine how this occurred, because there are numerous parallels

to the modern transformation of America from republic to empire. The “money madness” which eventually wrecked

the Roman Republic began to take hold after Rome had defeated its principal

rival Carthage and assumed hegemony over the Western world. After Carthage and its former colonies were

ruthlessly stripped of their wealth, Rome’s productive agrarian/craft economy

was subordinated to the financial manipulations of a moneyed elite, which

progressively reduced Rome’s middle class to debt peonage and its lower class

to outright slavery.

With slavery came the novel idea of absolute property rights. If the rights associated with property were

to be considered so unqualified as to efface the identity and dignity of

another human being, then all other restraints on their exercise must likewise

give way. Traditional notions that a person holds

property contingently as God’s Steward, subject to respecting the sanctity of

Nature and the welfare of the Community, came to be seen as hindering “free

trade”. Thus began the Orwellian

redefining of “Freedom” as the unbridled exercise of property rights for

personal gain, regardless of the consequent harm to others and pillage of the

planet.

This radical reframing of property rights relied on the emergence of

the analog self as the commanding element of the human Persona. While the true Selfhood of each individual is

inextricably linked that of his/her fellow humans, the Specter is disconnected,

“dwelling alone” in a narrative universe of its own making. Consequently, the Specter is blind to the

Reality that each generation holds the Earth and her resources as collective

heirs of past generations and in trust for future generations. No single person creates wealth out of

his/her efforts alone, but only thanks to the legacy of knowledge passed down

from our forebears and the advantages of living in a Community of cooperating

citizens. These benefits of a sustained

civilization belong to no one individual, but are the common patrimony our

species. So the idea that each person

acquires his property solely through his/her personal efforts – and hence is

absolutely entitled to exploit it as he/she sees fit – is a solipsistic

delusion fostered by the insular mind-space of the analog self. Hence, it’s quite fitting that the leading

modern expositor of this abominable creed should have chosen for herself the

name Ayin, which invokes the

“nothingness” of the Qlippot.

Turning once more to Rome’s faltering republic, there were still a few

brave souls among the Roman Tribunes who resisted the juggernaut of usury, most

notably the Gracchi brothers in the Second Century BC. Then began the now-familiar pattern of defaming

and murdering those public officials who cannot be bought off. After the assassination of the Gracchi, Rome

descended into a century of civil wars which ushered in the autocracy of the

Caesars, who ruled on behalf of the triumphant creditor oligarchs. Morphing into a Vulture, the Roman Eagle

became the universal emblem of hated oppression and iniquity, as Rome’s usurers

were set loose to prey upon the Empire’s provinces. Such was the setting for Christ’s first

sermon in Nazareth, and his proclamation of the Great Jubilee marked him for

death at the hands of his Roman overlords.

On the eve of his execution, Jesus warned his disciples of the coming

of false messiahs in the Endtime, and he associated their coming with a

particularly compelling image.

For wheresoever the

carcass is, there will the vultures be gathered together.[55]

To get the full import of this pronouncement, we must appreciate that

the Hebrew word for “carcass” has connotations that go far beyond the simple

meaning of a “dead body”. Nebelah can also signify an idol, as in

the following passage from the prophet Jeremiah:

And first I will

recompense their iniquity and their sin double; because they have defiled my

land, they have filled mine inheritance with the carcases of their detestable

and abominable things.[56]

From the root nabel, the

“carcass” is a vile thing that amounts to nothing, that comes to naught. So we can readily recognize that this

“carcass” partakes of the Vanities, that which is not just dead, but lifeless

and Life-negating – futile entities that fall short of actual existence, but

which exert an attraction on the spectral side of the human psyche. We can discern that Christ was referring to

the advent of the ultimate personification of the Specter, stepping out

Nero-like from his private stage into the arena of the world at large, an Idol

seemingly “bigger than life”, but inwardly devoid of Life. His magnetism is nearly irresistible, because

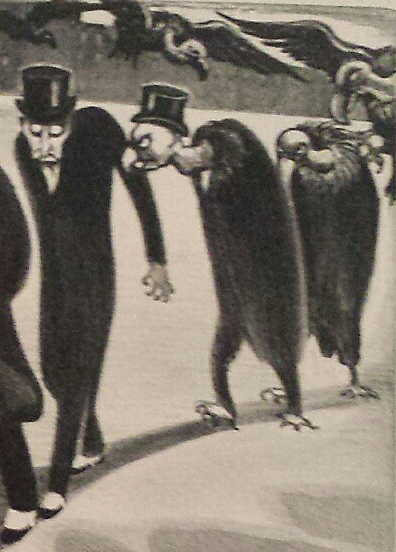

he draws to himself the “vultures”, the analog selfhoods operating all of us. And, of course, the culture of voracious

usury emboldens these spectral birds of prey to tear relentlessly at the fabric

of our collective Soul, like the fabled vulture ripping into the body of Prometheus.

[Below, a detail from a

lithograph by Hugo Gellert]

The Roman Empire eventually collapsed under the weight of debt, as the

usurious oligarchs used their political clout to transfer the burden of

taxation onto the lower classes, and a massive wave of defaults and

foreclosures reduced the general populace to a bare subsistence level. The financial collapse was so precipitous

that it dragged Western civilization down with it into several centuries of

“Dark Ages”, in which only the Catholic Church survived as an institution

capable of preserving, albeit selectively, the culture and knowledge of the

ancient world.

Although it took European societies about 500 years to recover from

the Roman debacle, there was a positive side to it. Usury and its dogma of absolute property

rights had fallen into total disrepute.

Lending at interest was proscribed both by civil law and canon law, and

although enforcement of the prohibition was sometimes lax, Western society

remained mostly free of usury throughout the Middle Ages. Perhaps better absorbing the lessons of Roman

history, the Moslem world extended their ban on usury into modern times, which

explains quite a bit about the so-called “clash of civilizations” we are

encountering today.

The Narrative of Usury

It’s about this time that the historical revisionism of the usurers

and their intellectual minions begins to take hold. In their rendering, which is still dutifully

recited by orthodox historical accounts, the Roman Empire collapsed because of

excessive taxation and barbarian invasions.

The Middle Ages is depicted as an era of serfdom, plagues and the suffocating

dominance of the Catholic Church.

Freedom and enlightenment were not revived until the Renaissance, so the

story goes. What actually went down was

altogether different.

It’s much easier to swallow this totally mendacious account of

medieval history if one has never visited Europe. Because a typical tourist in Europe spends

most of his/her time admiring the cultural magnificence of the Middle Ages –

the monumental architecture of the Gothic cathedrals, castles, chateaux,

universities and parliaments – the simultaneous dismissal of this era as

semi-barbaric requires some extremely dissonant thinking. What’s even more remarkable is that

virtually all of these magnificent edifices, these towering testaments to the

Human Spirit, were built with volunteer

labor. How was this possible, if we are

to believe that the medieval masses were miserable serfs, barely eking out a

living, still waiting to be liberated by “free” markets?

As a matter of fact, the medieval laborer had sufficient leisure time

to help build cathedrals and the wherewithal to visit faraway religious shrines,

such as Canterbury in England, which hosted some hundred thousand pilgrims each

year. Free of the burdens of usury, a

worker of the Middle Ages could provide for the needs of his family for an

entire year by working only 14 weeks.[57] Without the parasitism of the money-lenders,

funds were available for inventions and art, supporting an explosive flowering

of civilization from the 13th to the 15th Century, including

such giants as Dante and DaVinci, which blossomed into the Renaissance of the

16th and 17th Centuries.

Absent during this era were the grinding, hopeless poverty and chronic

semi-starvation of the lower classes which came in the wake of usury’s revival.

In light of the foregoing history, it’s worthwhile to reflect for a

moment on the depths of debt peonage to which America’s “99%” have sunk. One could infer that, given the technological

advances and productivity increases of the past 500 years, if the debt-free

laborer of the 15th Century could support a family on less than four

months earnings, his 21st Century counterpart should be able to do

so, even at a substantially higher level of consumption, with no more than two

months’ wages. And, in fact, the

statistics bear that out. Direct

interest payments – on mortgages, student loans, auto loans, credit card debt,

etc. – absorb over half of the income of a typical U.S. wage earner. Factoring in indirect interest payments, in

the form of government taxes earmarked for debt service, only about a third of

wage income is left to spend on food, clothing, transportation, health care,

and other basic needs.[58]

And, since approximately half the

prices paid for the latter items also reflect interest charges, the average

U.S. worker winds up forking over five-sixths of his/her income to the creditor

parasites, without whom he/she could enjoy the same standard of living by

working only two months out of the whole year.

If we focus in on last thirty years, during which all previous

restraints on usury have been swept away, we see this trend of parasitic

extraction accelerating exponentially.

In the thirty years from 1950 to 1980, U.S. worker productivity

approximately doubled, and so did average wages. But in the next thirty years from 1980 to

2010, although productivity again doubled, wages remained flat. Once unleashed, the voracity of the vultures

knows no limits: they have gone from

consuming the lion’s share of the wealth generated by mankind’s technological

progress to consuming it all. And, as

they hunger for still more, the years to come will see them driving working

families down below the subsistence level, as they have recently done in

Greece.

Returning to our “revisionist” historical survey, the Middle Ages was

a relatively peaceful period, partly because large-scale military operations

required a lot more money than governments could fund out of current

income. In the setting of the warring

city-states of 15th Century Italy, this was a bothersome impediment

to ambitious rulers. Responding to this

need, a new creditor oligarchy emerged, led by the Medici family of

Florence. Giving the devil his due, the

Medici must be acknowledged as brilliant financial innovators. Traditional usury was incapable of funding

modern warfare, because it depended on the transfer of physical assets, such as

precious metals and coins. What the

nascent war-machine required was a radical expansion of the money supply. This was accomplished by a revolution in

banking enabled by “double-entry” bookkeeping, in which a debt in one account

is offset by a credit in another, allowing extension of credit without the

exchange of physical coins. By this

method, a debtor’s promise to pay could be transformed into a banknote, which

could circulate as a form of currency, thereby “monetizing” the debt.

The double-entry bookkeeping innovation introduced by the 15th

Century Florentine bankers was a watershed event in the evolution of

usury. Before that, the growth of usury

was restrained by the limit of the money supply tied to precious metals. Now money could be created ex nihilo – literally “out of nothing” –

by a series of bookkeeping entries monetizing IOUs. Since wars could now be funded on credit

without any new influx of gold or silver, Renaissance Italy descended into a

centuries of bloody conflict among its city-states. Freed of constraint by a limited money supply,

a new and much more virulent strain of usury was unleashed upon the world, and

monetized debt began to drive out the traditional exchange-based forms of money

that had prevailed during the Middle Ages.

Medieval money, both in Europe and China, consisted primarily of

receipts or “tallies” for goods and services, rather than promises to pay. Such tallies were usually issued by

governments, who could thereby spend money into the economy without the need

for taxation. For instance, a prince in

need of a new carriage would pay the carriage-maker with tallies equivalent to

the value of the carriage, which the carriage-maker could then spend on food,

clothing, etc. Since the tally receipts and the exchanged

goods came into existence at the same time, their values balanced each other,

keeping medieval prices stable for many centuries. In England, for example, “tally sticks”

introduced by King Henry I in the 10th Century circulated as the

country’s principal money supply until the end of the 17th Century,

when their value amounted to some 14 million pounds. Such money, issued free of interest and

without governmental debt, funded an era of abundance and leisure which we

still recall as “Merrie Olde England”.

Since tally-type money could not be created without corresponding goods

and/or services, the money supply could not be inflated and deflated, as is the

cyclical pattern for debt-based money.

This brings us to a bit of American history which has been assiduously

ignored by the standard texts. Most of

us were taught in school that the America’s colonial Revolution was brought on

by excessive British taxation, with the Boston Tea Party as the meme that

implants this scenario in young minds. But

the writings of Benjamin Franklin tell a different story. Inspired by the British tally system,

Franklin instituted in the Middle Colonies a script currency which circulated

as receipts for goods/services provided to the colonial governments. By the mid-18th Century, the

American Colonies had become the economic wonder of the world, achieving a

level of prosperity and wealth seemingly inexplicable for a fledgling society